When I was five years old, my twin sister walked into the woods behind our house and never returned. The police told my parents they found her body, but I never saw a grave. Never saw a coffin. Just years of silence and a feeling deep in my bones that the story wasn’t truly finished.

My name is Dorothy. I’m 73 now, and my entire life has carried a missing piece shaped like a little girl named Ella.

Ella was my twin. We were five when she vanished.

Ella was sitting in the corner with her red ball.

We weren’t just twins who shared a birthday. We shared a bed, shared thoughts, shared everything. If she cried, I cried. If I laughed, she laughed harder. She was fearless. I followed her everywhere.

The day she disappeared, our parents were at work. We were staying with our grandmother.

I was sick. Burning with fever, my throat raw. Grandma sat beside my bed, pressing a cool cloth to my forehead.

“Just rest, baby,” she said. “Ella will play quietly.”

Ella was in the corner with her red ball, bouncing it against the wall, humming softly. I remember the dull thud, the sound of rain beginning outside.

When I woke up, something felt wrong.

Then nothing.

I fell asleep.

When I woke up, the house was wrong.

Too silent.

No ball. No humming.

“Grandma?” I called.

No reply.

She rushed in moments later, hair disheveled, her face tight with fear.

“Where’s Ella?” I asked.

“She’s probably outside,” she said. “You stay in bed, all right?”

Her voice trembled.

I heard the back door open.

“Ella!” Grandma called.

Then the police arrived.

No answer.

“Ella, you get in here right now!”

Her voice rose. Footsteps followed—fast, frantic.

I slipped out of bed. The hallway felt cold beneath my feet. When I reached the front room, neighbors crowded the doorway. Mr. Frank crouched down in front of me.

“Have you seen your sister, sweetheart?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“Did she talk to strangers?”

Then the police came.

Blue jackets. Wet boots. Radios crackling. Questions I didn’t know how to answer.

“What was she wearing?”

“Where did she like to play?”

“Did she talk to strangers?”

They found her ball.

Behind our house stretched a narrow line of woods. People called it “the forest,” as if it were endless, but it was just trees and shadows. That night, flashlights flickered between the trunks. Men shouted her name into the rain.

They found her ball.

That was the only clear fact I was ever told.

The search continued. Days passed. Then weeks. Time blurred. Whispers filled every room. No one explained anything.

I remember Grandma crying at the sink, repeating, “I’m so sorry,” over and over.

“Dorothy, go to your room.”

I asked my mother once, “When is Ella coming home?”

She was drying dishes. Her hands froze.

“She’s not,” she said.

“Why?”

My father cut in sharply.

“Enough,” he snapped. “Dorothy, go to your room.”

Later, they sat me down in the living room. My father stared at the floor. My mother stared at her hands.

“The police found Ella,” she said.

“Where?”

“In the forest,” she whispered. “She’s gone.”

“Gone where?” I asked.

My father rubbed his forehead.

“She died,” he said. “Ella died. That’s all you need to know.”

I never saw her body. I don’t remember a funeral. No tiny casket. No grave they took me to visit.

One day, I had a twin.

The next day, I didn’t.

Her toys vanished. Our matching outfits disappeared. Her name stopped being spoken in our house.

“Did it hurt?”

At first, I kept asking.

“Where did they find her?”

“What happened?”

“Did it hurt?”

My mother’s face would shut down.

“Stop it, Dorothy,” she’d say. “You’re hurting me.”

I grew up like that.

I wanted to scream, “I’m hurting too.”

Instead, I learned silence. Talking about Ella felt like setting off an explosion. So I swallowed my questions and carried them quietly.

I grew up like that.

On the outside, I was fine. Good grades. Friends. No trouble. Inside, there was a buzzing emptiness where my sister should have been.

“I want to see the case file.”

When I was sixteen, I tried to break the silence.

I walked into the police station alone, my palms sweating.

The officer at the desk looked up. “Can I help you?”

“My twin sister disappeared when we were five,” I said. “Her name was Ella. I want to see the case file.”

He frowned. “How old are you, sweetheart?”

“Sixteen.”

“Some things are too painful to dig up.”

He sighed.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Those records aren’t public. Your parents would need to request them.”

“They won’t even say her name,” I said. “They told me she died. That’s it.”

His expression softened.

“Then maybe you should let them handle it,” he said. “Some things are too painful to dig up.”

I left feeling foolish—and more alone than ever.

“Why dig up that pain?”

In my twenties, I tried one last time with my mother.

We sat on her bed folding laundry. I said, “Mom, please. I need to know what really happened to Ella.”

She went completely still.

“What good would that do?” she whispered. “You have a life now. Why dig up that pain?”

“Because I’m still in it,” I said. “I don’t even know where she’s buried.”

She flinched.

I became a mom.

“Please don’t ask me again,” she said. “I can’t talk about this.”

So I stopped.

Life carried me forward. School. Marriage. Children. A new last name. Bills to pay.

I became a mom.

Then a grandmother.

From the outside, my life looked full. But there was always a quiet hollow in my chest shaped like Ella.

This is what Ella might look like now.

Sometimes I’d set the table and catch myself placing two plates.

Sometimes I’d wake at night certain I’d heard a little girl whisper my name.

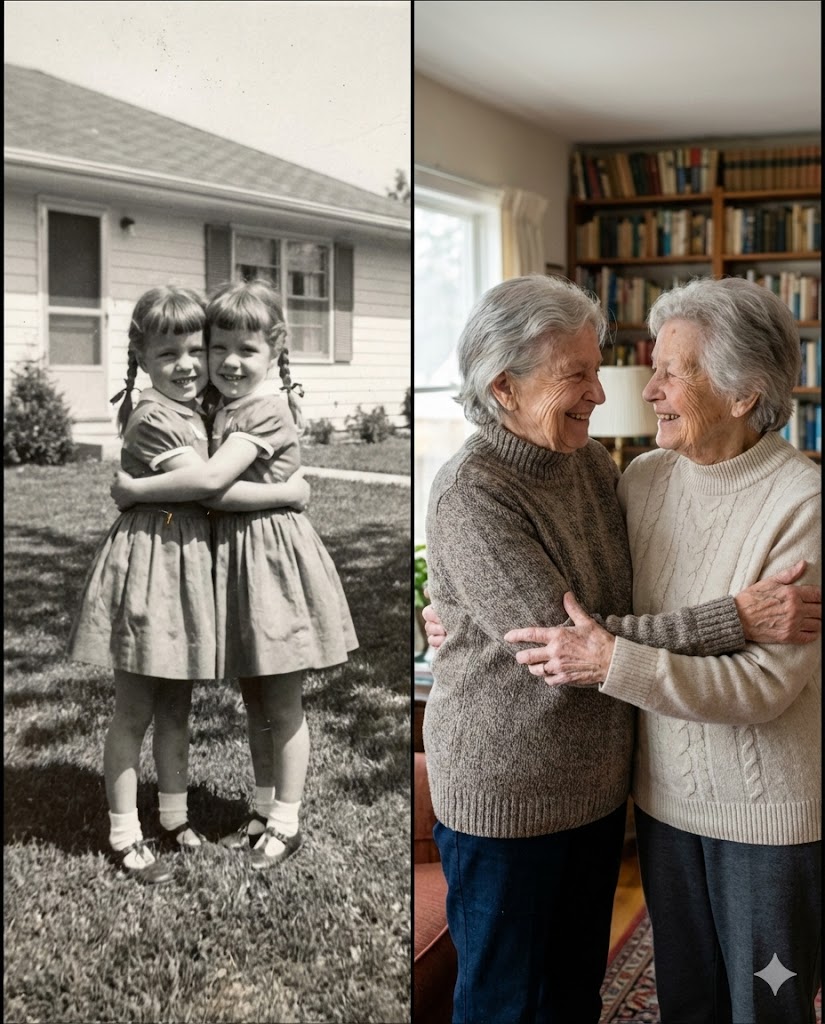

Sometimes I’d stare at my reflection and think, This is what Ella might look like now.

My parents died without ever telling me more. Two funerals. Two graves. Their secrets were buried with them. For years, I told myself that was the end of it.

A missing child. A vague explanation. Silence.

“Grandma, you have to come visit.”

Then my granddaughter got accepted into a college out of state.

“Grandma, you have to come visit,” she said. “You’d love it here.”

“I’ll come,” I promised. “Someone has to keep you out of trouble.”

Months later, I flew out. We spent the day setting up her dorm, debating towels and storage bins.

The next morning, she had class.

“Go explore,” she said, kissing my cheek. “There’s a café around the corner. Great coffee, terrible music.”

It sounded like something I’d say.

So I went.

The café was warm and crowded. Chalkboard menus. Mismatched chairs. The air smelled of coffee and sugar. I stood in line, barely reading the menu.

Then I heard a woman’s voice at the counter.

Ordering a latte. Calm. Slightly raspy.

The cadence hit me.

We locked eyes.

It sounded like me.

I looked up.

A woman stood there, gray hair pinned up. Same height. Same posture. I thought, That’s strange—and then she turned.

We locked eyes.

For a split second, I wasn’t an old woman in a café. I felt like I had stepped outside myself and was staring back.

I was looking at my own face.

I moved toward her.

Older in some ways. Softer in others. But unmistakably mine.

My fingers went numb.

I stepped closer.

She whispered, “Oh my God.”

My mouth spoke before my mind could stop it.

“Ella?” I choked out.

“My name is Margaret.”

Her eyes welled up.

“I… no,” she said. “My name is Margaret.”

I pulled my hand away.

“I’m sorry,” I rushed out. “My twin sister’s name was Ella. She disappeared when we were five. I’ve never seen anyone who looks like me like this. I know I sound crazy.”

“No,” she said immediately. “You don’t. Because I’m looking at you and thinking the same thing.”

Same nose. Same eyes.

The barista cleared his throat. “Uh, do you ladies want to sit? You’re kind of blocking the sugar.”

We both gave shaky laughs and moved to a nearby table.

Up close, it felt even more unsettling.

Same nose. Same eyes. The same small crease between the brows. Even our hands looked identical.

She curled her fingers around her cup.

“I don’t want to freak you out more,” she said, “but… I was adopted.”

“If I asked about my birth family, they shut it down.”

My chest tightened.

“From where?” I asked.

“Small town, Midwest. Hospital’s gone now. My parents always told me I was ‘chosen,’ but if I asked about my birth family, they shut it down.”

I swallowed hard.

“What year were you born?”

“My sister disappeared from a small town in the Midwest,” I said. “We lived near a forest. Months later, the police told my parents they’d found her body. I never saw anything. No funeral I remember. They refused to talk about it.”

We just stared at one another.

“What year were you born?” she asked.

I told her.

She told me hers.

She let out a trembling laugh.

Five years apart.

“We’re not twins,” I said. “But that doesn’t mean we’re not—”

“Connected,” she finished.

She drew in a slow breath.

“I’ve always felt like something was missing from my story,” she said. “Like there was a locked room in my life I wasn’t allowed to open.”

“My whole life has felt like that room,” I said. “Want to open it?”

We exchanged numbers.

She let out a shaky laugh.

“I’m terrified,” she admitted.

“So am I,” I said. “But I’m more scared of never knowing.”

She nodded.

“Okay,” she said. “Let’s try.”

We exchanged numbers.

I searched until my hands trembled.

Back at my hotel, I replayed every moment my parents had shut me down. Then I remembered the dusty box in my closet — the one filled with their papers I had never touched.

Maybe they hadn’t told me the truth out loud.

Maybe they’d left it behind in writing.

When I got home, I dragged the box onto my kitchen table.

Birth certificates. Tax records. Medical files. Old letters. I searched until my hands trembled.

My knees nearly buckled.

At the very bottom lay a thin manila folder.

Inside was an adoption document.

Female infant. No name. Year: five years before I was born.

Birth mother: my mother.

My knees nearly buckled.

Tucked behind it was a smaller folded note, written in my mother’s handwriting.

I cried until my chest ached.

I was young. Unmarried. My parents said I had brought shame. They told me I had no choice. I was not allowed to hold her. I saw her from across the room. They told me to forget. To marry. To have other children and never speak of this again.

But I cannot forget. I will remember my first daughter for as long as I live, even if no one else ever knows.

I cried until my chest ached.

For the girl my mother once was.

For the baby she was forced to surrender.

“It’s real.”

For Ella.

For the daughter she kept — me — who grew up surrounded by silence.

When I could finally see clearly again, I photographed the adoption record and the note and sent them to Margaret.

She called immediately.

“I saw,” she said, her voice shaking. “Is that… real?”

“It’s real,” I said. “Looks like my mother was your mother too.”

We did a DNA test to be sure.

The silence between us stretched on.

“I always thought I was nobody’s,” she whispered. “Or nobody who wanted me. Now I find out I was… hers.”

“Ours,” I said. “You’re my sister.”

We did a DNA test to be sure. It confirmed what we already knew: full siblings.

People ask if it felt like some huge, joyful reunion. It didn’t.

It felt like standing amid the wreckage of three lives and finally understanding the shape of the damage.

We compare childhoods.

We’re not pretending we suddenly became best friends. You can’t compress seventy-plus years into a single coffee.

But we talk.

We compare childhoods. We send photos. We point out small similarities. And we face the hardest part too:

My mother had three daughters.

One she was forced to give away.

One she lost in the forest.

Pain doesn’t excuse secrets, but it explains them.

One she kept and wrapped in silence.

Was it fair? No.

Can I understand how someone breaks under that weight? Sometimes, yes.

Knowing my mother loved a daughter she wasn’t allowed to keep, another she couldn’t save, and me in her fractured, quiet way… it changed something inside me.

Pain doesn’t excuse secrets, but it explains them.